I want to start this year by referring to my values and why I do what I do.

I do get distracted and lose motivation at times and that’s why It’s important that I have an interested audience that I care about and want to show up for. THANK YOU.

Here are some words that I get to tweak and reorganize, edit and revise throughout the months. Learning is a constant and I hope I receive feed back and any thoughts from all you fabulous people.

Why am I interested in geology? Because I’m curious. I want to understand the underpinnings of where I am and it’s ancient history. It offers me a fulfilling sense of security, of stability and an inherent survival ability and how to be in unison with the natural world.

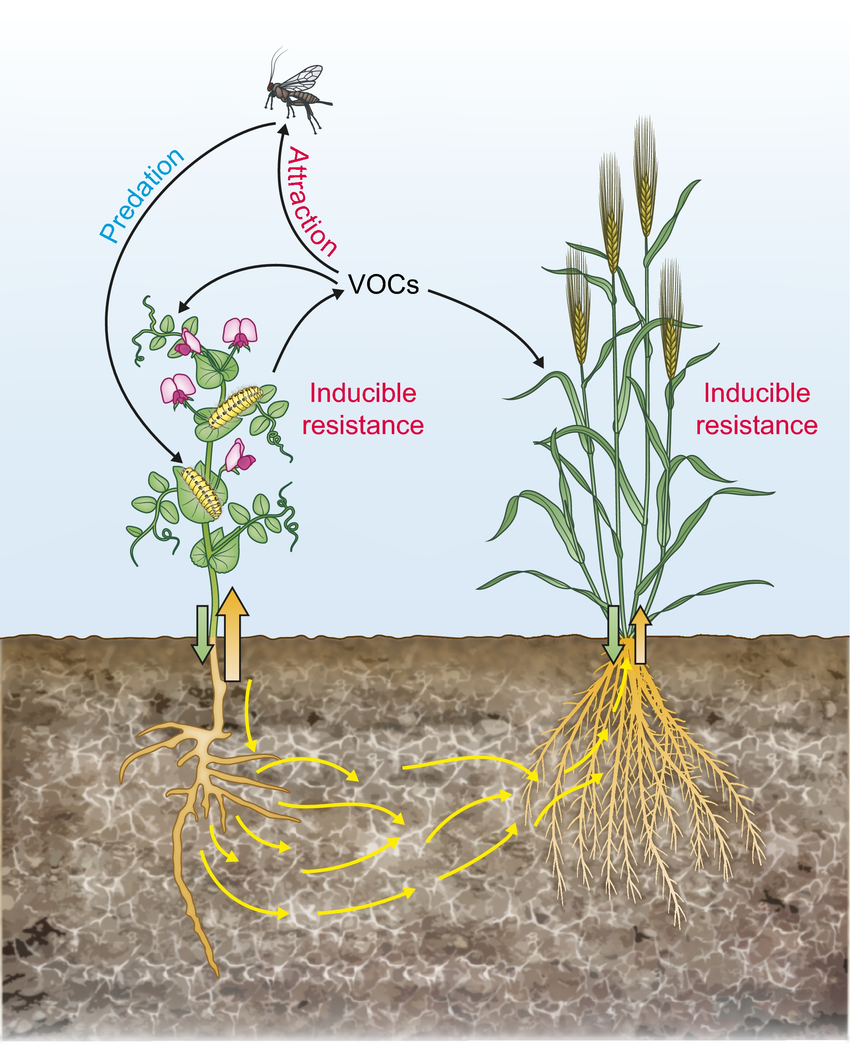

I’m interested in plants because it’s something that I can nurture and observe

I recently listened to an interview with Jane Goodall that was recorded to be shared after her death. I found it deeply moving. Her lifelong commitment to care, responsibility, and attention to the living world echoes many of the questions that have shaped my work over the past several years.

My practice has long been influenced by geology and landscape. In 2017, while traveling in Iceland, I was struck by the immensity of its geologically dominant terrain. The scale, time, and force embedded in that landscape awakened a sense of wonder and imagination that stayed with me.

That sense of wonder gradually led me toward more difficult questions. As my work evolved, I began researching mining, extraction, and industrial processes—particularly those tied to the minerals and elements used in everyday technologies. A major project in 2021 grew out of this research.

Visiting mining sites and quarries, I noticed a recurring pattern: we take what we need and often leave the consequences behind. The resulting landscapes—scarred, depleted, or abandoned—reflect a broader habit of disregard, one that feels increasingly urgent to confront.

A visit to a Quarry in Somerset UK.

Lately, my focus has shifted from extraction to care. I’m interested in what happens after damage has been done, and how responsibility might take shape through repair. While nature has a remarkable capacity to reclaim disturbed land, I believe there is also room for conscious human participation—acts of restoration that acknowledge harm and support renewal.

This ongoing shift continues to inform my studio work, shaping both its material concerns and its intentions.