Geology—rock and stone, the very skeleton of the land we live on—has always inspired me. Beneath our feet lies not only a foundation but also a record of history: layers formed over millions of years, reshaped by human activity through mining and quarrying. When we bring what is buried to the surface, we often leave scars on the land. My work explores this tension—between what is hidden and revealed, stable and disrupted—and how these ideas can be expressed visually through mixed media while learning about abandoned mine remediation

My two artist residencies in Iceland were pivotal in connecting my practice to landscape in a deeper way. They also introduced me to biodesign, specifically the process of phytoremediation: using plants to detoxify polluted soil. This method has growing importance in the rehabilitation of abandoned mines and quarries worldwide.

I have explored several sites marked by extraction: silver mines in Nevada (USA), left as vast open pits on what are now government-issued Indian reservations; a lead mine in the Mendips (UK); a deserted copper mine in southern Ireland; and countless quarries that remain as empty voids, visible even through satellite images online. These places are not just industrial remnants—they also carry environmental legacies in the form of toxic tailings, where heavy metals such as lead, arsenic, and cadmium persist in the soil long after mining has ended.

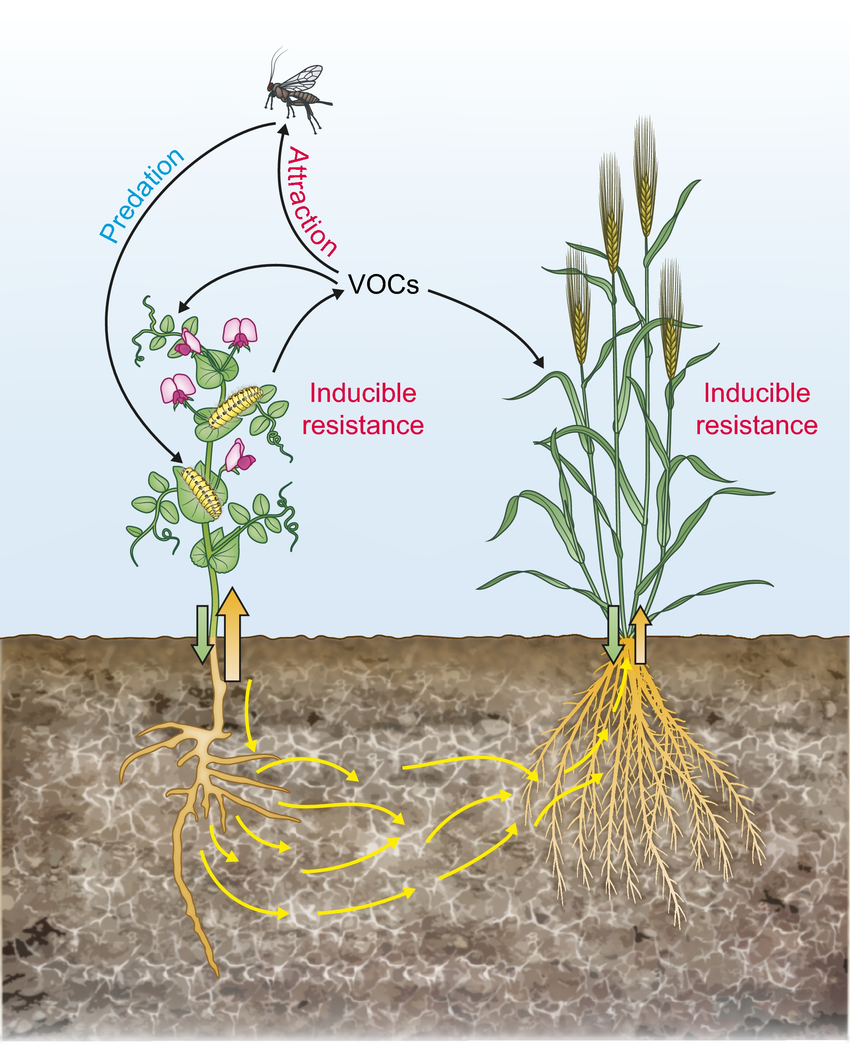

Phytoremediation offers a promising, nature-based solution. Certain plants—including grasses, trees, and shrubs—can take up contaminants through their roots and either store, transform, or stabilize them. Tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea), for example, is known for its ability to stabilize soil structure while absorbing pollutants. Even more compelling is its symbiotic relationship with mycelium, the underground fungal networks that extend root systems and enhance the breakdown and redistribution of toxins. Together, these living systems form a cooperative network that gradually restores ecological balance to damaged ground.

What fascinates me most is the hidden nature of this process: the cellular-level exchanges between roots, fungi, and soil chemistry. These invisible interactions represent both a scientific strategy for detoxifying landscapes and a metaphor for resilience—quiet systems working in collaboration to heal what has been poisoned and disturbed.