The Hide Residency: Notes from the Beginning

As I begin my residency at The Hide in the third week, I feel a loosening—an opening in approaching the work. Much of this shift comes from a recent critique and discussion with Alice, which helped me reframe where I’m heading.

Residencies always bring the environment into the work and shows up as if on its own accord, shaping how I work. This time, though, I’m merging that response with a project: exploring phytoremediation, the use of plants and trees to detoxify soil on abandoned mine and quarry sites. At first, I had no idea how to weave this scientific concept into my art practice. The challenge has been finding links between the way I naturally work—mark-making, layering, experimenting—and the research itself. It requires patience, which has not always been my strength, but I’m beginning to develop it through walking meditations and noticing their benefits.

Digging Beneath the Surface

My overarching interest has always been with what lies underneath: the hidden, the honest, the overlooked value of the earth. Mining and quarrying, after all, are about tearing geology from below and building with it above—an ancient yet strangely unsettling concept.

This curiosity runs deep. As a small child, I would bury small dead animals (birds and mice killed by the many cats most likely) in marked graves, later digging them up to see what had changed. What remained of feathers or fur? What did the bones look like? That same fascination with transformation, with what lies beneath, continues to inform my work.

Materials in Play

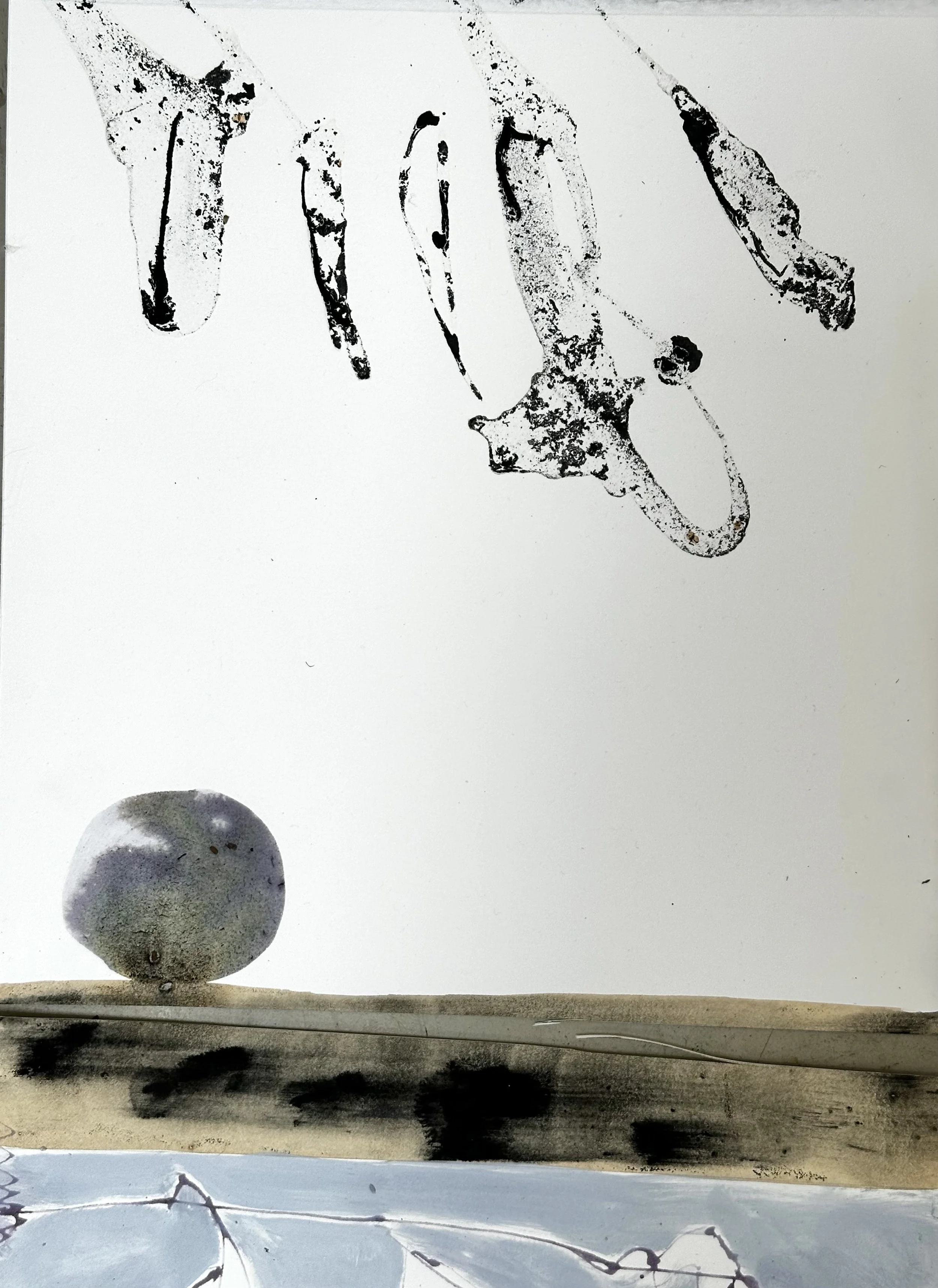

Paper, drawing, and painting are my familiar foundations, but here I’ve been drawn into more dimensional work using willow sticks readily available on site. Interestingly, willow itself is a plant known to aid phytoremediation, helping break down arsenic, cadmium, and lead in contaminated soils. Tall fescue, another phytoremediator, thrives around abandoned mine sites, working with underground mycelial networks to process toxic chemicals in water and soil.

So, in both research and practice, I’m working with ideas of buried becoming unburied, of transformation beneath the surface, led by roots, fungi, and time.

Process and Approach

How would I summarise my process? Perhaps like this:

Investigation as practice—letting the work guide me, as much as I guide it.

Mark-making as inquiry—each gesture exchanged for knowledge, information, or insight.

Visual language as emotion—reaching into consciousness where words fall short.

There’s also a ritual element, a leaning into the “discovery & magic in the science” of what plants can do. It feels close to an Indigenous perspective—acknowledging and giving gratitude for what the earth and its systems offer—so that the work is not just mine, but part of something larger.

Looking Ahead

The question I hold now is how these thoughts and experiments can evolve into something visually clear without becoming overly complicated—something playful, engaging, and alive for me to work with and share.